The Elephant and the Rider

Joachim Stempfle

Yes, change is instrumental in keeping up with the fast-paced times we live in. Wouldn’t you just love to push a big red button, and watch the transformations you want to see in your organization happening instantly? While this might sound like a good idea, we all know it is not that easy. Any change on the outside requires us to change something within ourselves. And to enable change within, we will need to enlist an unlikely ally: our emotional self.

A mistake I made recently illustrates what happens if we don’t attend to the emotional self. I recently had great conversations with some enthusiastic colleagues about a change we would like to bring about in our organisation. We inspired each other and came up with more and more beautiful ideas. Then, we shared these thoughts with a larger group of people. However, their reactions were lukewarm. While some people saw the merit in the ideas, others were less than eager, and pointed out why our new plans would not work. We could not agree on a common approach and in the end, we had to postpone the discussion. We all felt tired and unsatisfied.

What went wrong?

First, the meeting was scheduled on a Friday afternoon — when everyone was already tired from a long week full of virtual meetings. I could have noticed the looks on people’s faces — they were ready for the weekend. The last thing people wanted to hear on this Friday afternoon was a plethora of ideas about what we could do next.

Second, I was focused on sharing rather than listening. As a result, others did not feel listened to.

When encountering pushback, I tried even harder to convince the colleagues, only to meet even stronger pushback.

Why did this not work?

Simply put: We were all going on our emotional autopilots. This phenomenon is called “emotional hijacking” — our emotions took over, and we found ourselves resorting to assertive or defensive behaviors.

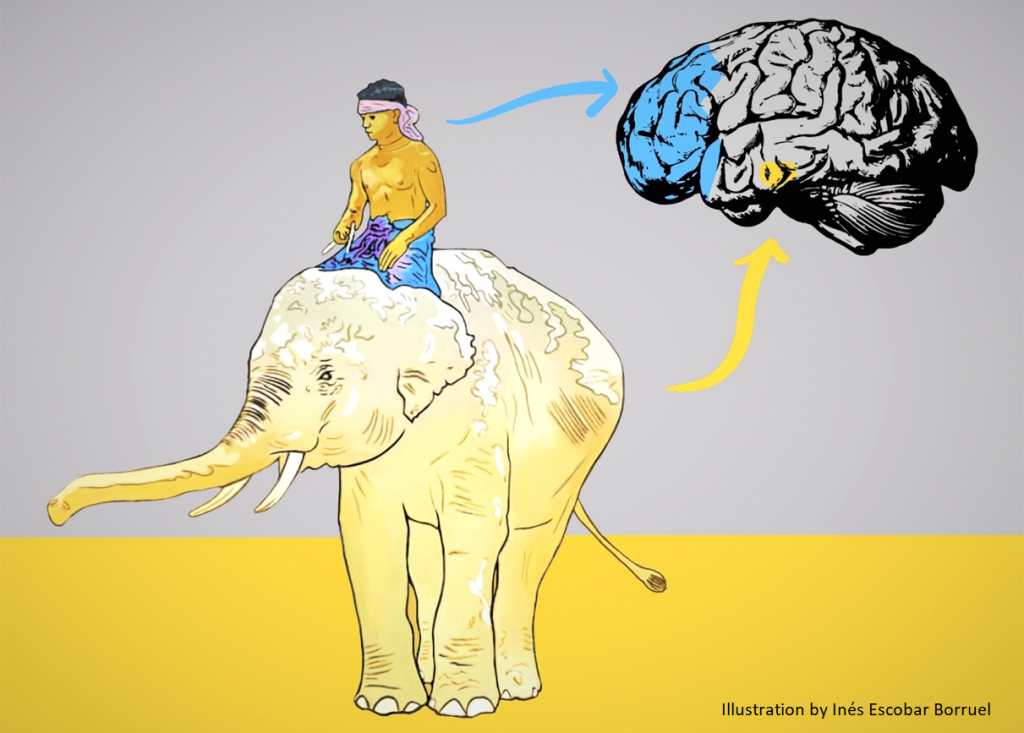

The metaphor of the Elephant and the Rider nicely sums up the relationship between our rational and our emotional self. Nobody knows exactly where the metaphor originated, although it can be traced down to The Dhammapada (c. 300 BC). In this ancient Buddhist scripture, an elephant represents selfish desire, and a human trainer represents the discipline that brings harmony to the mind. More recently, American sociologist Jonathan Haidt (2006) linked this analogy to modern neuroscience.

Picture an elephant, moving steadily and confidently along a dirt road. Atop of it, there is a comparatively small rider guiding the animal. From afar, it may appear that the rider is in full control of the situation. However, as soon as an obstacle appears in its way (for instance, a small animal) the elephant might take control and try to run in a different direction to avoid it. This metaphor beautifully illustrates the interplay between our old brain (linked to emotions, represented by the elephant) and our new brain (linked to more complex cognitive functions, and represented by the rider).

In the above illustration, two cerebral regions have been highlighted: the prefrontal cortex (in blue) and the amygdala (in yellow). Behavioral change efforts often fail because they focus solely on the rider — our conscious and rational mind, situated in the prefrontal cortex — while leaving our unconscious and emotional mind (typified by the amygdala) unattended. In other words, we ignore the elephant.

How do we enlist the elephant as an ally?

It turns out that elephants are social, playful and curious creatures. Yes, elephants can be stubborn, but if we acknowledge the elephant and work with it rather than ignoring and scaring it, it can become an enthusiastic ally.

So, recognizing and appreciating the elephant, what could I have done differently?

First, I could have scheduled the meeting in the morning, rather than on a Friday afternoon. Tired and hungry elephants will be grumpy — let’s talk about important things when our elephants are rested and well-fed.

Second, I could have reflected on my own goals and emotions before going into the meeting. I might have recognized that my own elephant was over-eager to move forward and in danger of moving too fast, overwhelming people.

Third, we could have started the meeting with a moment of mindful connection, checking in with each other on how we are doing and letting everyone share what is on their plate. This would have enabled all of our elephants to calm down, relax and connect with each other. It would have also enabled me to understand what was on other people’s plates.

When encountering pushback and challenges, I could have recognized the emotional needs of others. When someone pushes back, is it because they disagree, or is it because they feel overwhelmed, scared, or tired? If that is the case, bringing in more compelling arguments is not very useful — it would be wiser to explore what the other person is feeling, understanding their concerns, and giving the elephants time to digest and calm down.

In times of pandemic, stress and tensions run high. Do we keep adding to the tension, or do we start being mindful of our elephants? If we approach each other as human beings, attending to our own and others’ emotional needs, we have a much better chance to connect and collectively make the changes that are required. Imagine what would be possible if we all became empathetic elephant caretakers.

(written with the support of Inés Escobar Borruel)