2+2=5?

Or: What makes a great team

Joachim Stempfle

A leadership team I have been working with for five years went through a remarkable evolution. When we started out, I had only a 2-hour slot to discuss the results of an employee engagement survey with the team. At this stage, the team was a typical “team of leaders”: Strong egos, everyone managing their own silo, a “polite truce” between people. Interactions tended to be rather political and superficial.

However, something happened during these 2 hours. Triggered by feedback from employees, the team started to have an honest conversation about the gap between who they wanted to be, and how employees actually perceived them. We ended up speaking for 4 hours and in the end, the team agreed to schedule an off-site. Over the next 5 years, we went deeper and deeper. Team members gradually started to open up to each other, sharing about themselves, their ideas and dreams, their challenges, and their vulnerabilities. They started to exchange feedback on expectations, addressed tensions, and developed a culture of trust and honesty. Then the team jointly defined a courageous and powerful vision and strategy for their organisation. As people were thinking beyond their siloes for the best of the organisation, they were looking to bring out the ultimate potential of their organisation, in service of their customers. The team was quite diverse and everyone brought a unique perspective in – the resulting vision and strategy were groundbreaking, but also well thought through. The team was then able to steer the organisation through an organic transformation process, which enabled the organisation to renew its purpose as well as its operations. This required the leadership team to have difficult conversations – at one point the team realized that none of their current roles would be required in the new operating model they had designed, and they put themselves at risk.

This journey exemplifies that not all teams are created equal. Some teams enable us to bring our full selves in, transcend our egos, and co-create novel solutions. Such teams enable both co-creation and co-evolution of the team members. In such teams, the sum is more than its parts – 2+2 = 5. On the other end of the spectrum, a dysfunctional team can be an endless source of distress and anxiety.

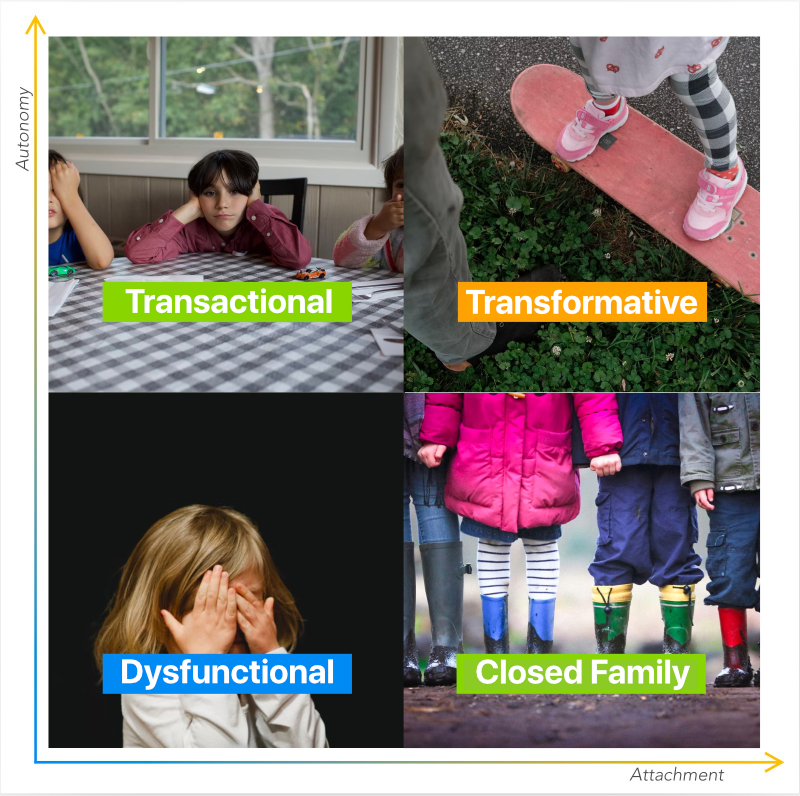

In an earlier post, we discussed two fundamental human needs: The need for autonomy and the need for attachment. How do these needs play out in a team setting?

With a simple 2×2 grid, we can categorize teams by the extent to which they fulfil the individuals’ needs for attachment and autonomy.

Everyone loses: The simple recipe for dysfunctional teams

Many of us have at one point in our lives and careers experienced or observed a dysfunctional team. In a dysfunctional team, no one gets their needs met. The defining element of a dysfunctional team is that team members are mutually blocking their needs for autonomy. Everyone is trying to get their needs met, but as people are blocking each other, the resulting ongoing battle damages relationships and trust, so the need for attachment is equally frustrated. As a result of the pain that people mutually inflict on each other, the team members increasingly see each other as a threat. This creates a lose/lose situation: Everyone fights for themselves, no one supports each other, and no one takes energy out of the relationship. In dysfunctional teams, there is little mutual empathy or understanding between the parties. Team members become mutual stressors for each other and trying to maintain or repair the relationship tends to absorb much of the team members’ energy.

Unfortunately, dysfunctional teams are not that rare. Usually, they do not start out as dysfunctional. Often a dysfunctional dynamic (like one person over-driving for autonomy) gets exacerbated under stress. An external threat triggers people in their survival strategies, some people end up pushing or dominating others. The reaction is push-back or withdrawal, and the result is a deadlock. That is why it is so dangerous when small conflicts stay unresolved, leaving the problem to fester until it has ballooned out of proportion.

Why do people stay in dysfunctional relationships when they are so detrimental? Psychologists provide three different answers. Some people have grown up in dysfunctional relationships – they are expecting relationships to be like that and when this is confirmed by reality, they feel a strange sense of security. For others, it is simply “the devil you know …” – we are social creatures, and many of us prefer to be in a dysfunctional relationship over being alone. Finally, dysfunctional relationships drain our confidence – they make us feel small and incapable. Hence, when you are stuck in a dysfunctional team, it is hard to find the courage to either transform the team or leave the team.

In it for the money: Transactional approaches

Political intrigue is a popular theme in Hollywood movies, but this tendency to work together only as long as it serves one’s own egocentric goals is not unique to politics. Many people have been educated to see life as a zero-sum game, in which the goal is to maximize one’s own personal gain and self-interest.

In transactional teams, the bond that keeps the team together is the self-interest of all parties. Everyone is pursuing their own individual goals in the context of the team. As long as the team provides a good platform to realize one’s personal career ambition, people will remain part of the team – but in essence, team members look at each other as competitors rather than as partners.

In transactional teams, there is a focus on fulfilling the individual members’ needs for autonomy. Other team members are evaluated in terms of being either helpful or harmful to the pursuit of one’s personal goals. Usually, some kind of truce emerges – members compromise somewhat on their individual goals when they recognize that it is in their best interest to do so. Often, implicit deals such as “scratch my back and I scratch yours”, or “don’t meddle with my area and I won’t meddle with yours” emerge. The need for deep connectedness and trust, however, is not being fulfilled. Transactional relationships can survive and function for a surprisingly long time, but usually, there is a sense of stagnation. Everyone carries on with their work, but nothing transformative is being built together.

Compared to a dysfunctional team, this type of team is not fully dysfunctional. Regarding the performance that is possible in such arrangements though, a lot of potential is left unfulfilled. The team is only able to make decisions that enable everyone to maximize their personal goals – no one is willing to sacrifice for the greater good. This is why in transactional teams, you will often find some units over-resourced while others are severely under-resourced – resourcing typically reflects the power and status dynamics in the team rather than business logic.

Transactional teams often emerge in highly competitive or individualistic cultures. The prevalence of individualism and materialism unfortunately has left many to believe that maximizing self-interest and personal gain will make us happy. The “homo oeconomicus” paradigm, which in a reductionist fashion assumes that people generally strive to maximize their own self-interest, has created the false impression that in order to be happy, people should primarily focus on their individual gain. Narcissism is on the rise, leaving many people “lonely in the crowd” – they might be part of many groups, but these groups are more a comparison group for social status.

All we need is harmony: It might seem like bliss, but it suffocates agency and creativity

Especially when people have experienced dysfunctional or transactional teams before, being part of a team where genuine care about each other is the norm often feels like a relief. In a team that resembles a closed family, the need for harmony is so overwhelming, however, that the individual disappears almost completely. There is often no more “I”, but only a “we”.

Connectedness is the sole focus here, autonomy on the other hand is discouraged. For a time, closed family-type teams often have great harmony. You are being supported by others, but the cost is the suppression of one’s own autonomy. This harmony is therefore a fragile state. It can only be maintained if people subordinate themselves, their needs, and their growth to the group. In closed family-type relationships, people are expected to do whatever it takes to “fit in”.

But without room for individuality, there is no opportunity for self-discovery. There is no room for meaningful personal growth. Challenges or disagreements are frowned upon. In such teams, diversity cannot flourish. And as there is no room to re-negotiate relationships, the team, as well as the individual members, tend to be stuck in time – nothing grows, nothing changes.

A personal experience comes to mind which explains why such a team indeed resembles a closed family. I did some work in a cultural context where family is all-encompassing. In this culture, people tend to spend 5-7 evenings a week with the larger family. Weekends are spent entirely with the extended family, with large feasts being hosted every weekend for up to 70 people. When I asked a person I was working with why people in this culture struggle so much with addressing disagreements, giving feedback, or resolving conflict, she gave the obvious answer: As relationships are so close and you see people every day, there is an unspoken rule not to do anything that might damage relationships or disrupt harmony. Anyone who speaks out is frowned upon. In a coaching interaction with another person in this cultural context, I learned about her lifelong struggle. She tried to carve out a life for herself that would enable her to leverage her unique passion and strengths. However, this went against what the family had envisioned for her. She realized that sooner or later she would need to make a difficult choice – she would either need to leave the family in order to live her dream or sacrifice her autonomy and take the path that others had carved out for her. Needless to say that having to choose between who you really are and staying connected to those you love is a tough choice that can leave people paralyzed and stuck for years.

More than the sum of its parts: How psychological safety enables transformative relationships

There are teams out there that bring out the best in people. People who have experienced such a team usually treasure the memory for years. But what makes these teams special? Transformative teams enable all team members to fulfil both the need for connectedness and the need for autonomy. They provide an emotional Homebase while encouraging, enabling and challenging people to become the best version of themselves.

The hallmark of such teams is psychological safety. Contrary to popular belief, psychological safety does not equal harmony. According to Amy Edmondson, psychological safety is the shared belief that the team is a safe space for interpersonal risk-taking. In other words, there is such a high level of trust between people that no one watches their back. No one hides or plays a role. People open up and show up as they are. This also enables people to give honest feedback to each other, share expectations transparently, and voice disagreements openly. Everyone is challenged, yet everyone feels safe.

Achieving this is only possible if there is a high level of mutual trust – this needs to be built over time. In teams with high psychological safety, people know each other deeply. They know each other’s life stories, needs and goals, strengths and weaknesses. No one pretends to be someone else. Such teams spend a considerable amount of time getting to know each other to build a strong foundation that can carry the relationship in times of hardship or conflict.

Opening up to others to this extent implies taking risks and requires a high level of personal maturity. In teams that do not yet have psychological safety, people often express the concern that they can only show vulnerability if they are certain that the information is not going to be used against them. This creates a “chicken and egg” type problem. Taking a leap of faith, trusting in the good intention of others, is required to co-create psychological safety. Leaders have a key role to play – they will need to take the first step and role model showing vulnerability for others to follow suit.

In the same way that a large tree needs strong roots to stay upright, a transformative team relies on trust and authentic relationships to keep it stable. This requires regular rituals that enable authentic interactions in a positive and constructive setting. Without such recurrent dialogue, it is hard to maintain psychological safety. Rather than educating people about psychological safety, we should invest in actually building it in intact teams by deliberately creating and facilitating a regular rhythm of authentic interactions.

In transformative teams, everyone is being transformed through the relationship, and as a result, the team is able to transform reality. This is why I like to call such teams transformative. As team members open up their hearts and minds to each other, they are being touched deeply by others. This leaves no one the same. In a transformative team, people will bring all of their perspectives, ideas and skills. As the atmosphere is highly inclusive, new insights and truly creative and novel solutions will emerge naturally and spontaneously. This enables the team to subsequently transform reality. Anyone who has been able to experience or facilitate a truly transformative interaction will be deeply touched by the magical power of such interactions. In my perspective, any business transformation needs to start with turning the leadership team into a transformative team.

Transformative teams also encourage people to venture out, make their own experiences, pursue tasks outside of the team and come back to share the learnings and the wisdom with the team. The team acts as a psychological Homebase, but it does not constrain people – it encourages individual agency and growth. Besides coming together to master collective challenges, everyone also owns their own personal journey and the challenges and trials that are theirs to take. Team members challenge each other to take ownership of what is theirs, but they also mutually support each other’s personal growth. This is why such a team, contrary to the closed family, never feels like a “closed shop”- there is an atmosphere of openness and curiosity.

The dynamic nature of transformative teams also implies that relationships in a transformative team are never static, but in a constant dynamic equilibrium. With each individual in the relationship developing continuously, relationships will need constant adjustment to stay relevant and functional. As people grow, leadership might fluctuate among team members, depending on situational requirements, skills and maturity level of team members.

Often the members of a transformative team will themselves incubate transformative teams in other parts of the organisation. The powerful experience they have in their home team enables them to replicate the experience in teams they are leading or participating in. As a result, transformative teams become an incubator for organisational transformation and growth.

Transformative teams offer great potential, but they require intentional building and continuous maintenance. But this effort pays large dividends. A good starting point is to ask yourself questions such as:

- What does my team feel like? Is it dysfunctional, transactional, is it a closed family, is it transformative?

- How can we encourage each other to share more deeply about ourselves?

- How do we enable everyone to bring out their true self, and become the best version of themselves?

- How can we move past ego-driven agendas and focus on what the team must create together – for the benefit of others?

- How do we build a culture of radical openness and honesty?

References and Resources for your interest:

In this article, we draw on the work of Paul Gilbert, Amy Edmondson, and Robert Wright. For further reading, we recommend:

-

- Conversation with Paul Gilbert on Creating a Compassionate World

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

- Gilbert, P. & Choden (2014): Mindful Compassion: How the Science of Compassion Can Help You Understand Your Emotions, Live in the Present, and Connect Deeply with Others.

- Wright, R. (2001). Nonzero: the Logic of Human Destiny.

This article was written with the support of Jonas Börnicke.